Mira Weimer is a NELC major graduating this year. She studies the Arabic language, and following graduation, she will return to Berkeley, California, to cook at Chez Panisse restaurant

Mira Weimer's senior essay is a sort of synthesis of the books, topics, and themes that she has focused on while studying in the NELC department of UW. Under the guided supervision of Professor Hamza Zafer, her essay looks at archetypal themes of prophecy, focusing primarily on prophecy in the Hebrew Bible, and its Late Antiquity retellings and interpretations. What began as an essay looking at individual prophetic instances of compliance, resistance, and rejection, has morphed into an essay that looks mainly at the prophet Jonah/Yunus, and his unique denial of prophetic tasks.

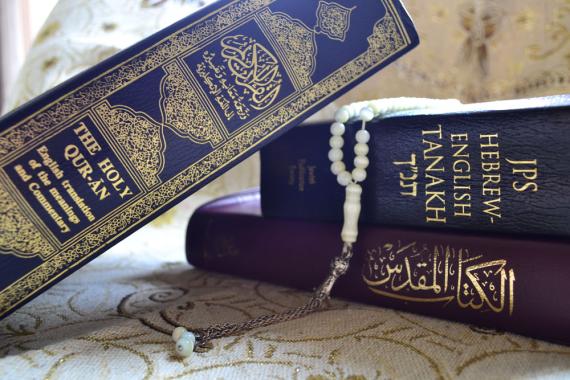

Set against the backdrop of stories of prophecy in the Hebrew Bible, the Qur’an, and the Peshitta, this essay analyzes the reasoning behind the inclusion of Jonah as a prophet, and the ways in which his prophecy challenges and undermines preconceived prophetic archetypes. Jonah appears to be the standalone prophet of rejection, with a unique foresight into God’s forgiveness of the Ninevites, and

Focusing on interpretations from Late Antiquity and modern day, this essay attempts to understand the ethical implications and meanings of Jonah’s prophecy, and the ways that interpreters took liberties to rationalize and explain the chapter. Jonah’s chapter is traditionally read on the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, as an example of God’s endless forgiveness. However, some Biblical scholars view Jonah’s chapter as a form of satire–a story poking fun at the seemingly unconditional piety of prophets, despite horrendous situations (i.e., Abraham’s ready willingness to sacrifice his son at the behest of God, or Hagar’s agreement to live in a barren desert with her son, after Sarah casts them out).

Through analyses of retelling and commentary, Weimer investigates the myriad duality between prophetic representation, and their lasting effects on Biblical interpretations of morals, ethics, and understanding.