-A report by Sergen Avci

Dr. Didem Havlioğlu, a literary historian and Associate Professor at Duke University who works on women and gender in the Islamicate world, gave a fascinating talk titled “Performance, Subversion, and Gender-Bending in Ottoman Poetry” on April 18th, 2024. With this talk, Dr. Havlioğlu contributed to the Walter G. Andrews Memorial Lecture Series hosted by the Turkish and Ottoman Studies Program in the Department of Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures. Her lecture delved into the intricate field of early modern Ottoman poetry, exploring concepts of gender, performativity, and marginality, with a particular focus on the woman poet Mihrî Hatun (c. 1515). Dr. Havlioğlu successfully illuminated the experience of being a woman poet in early modern Ottoman court culture, scrutinizing Mihrî Hatun’s poetry alongside narratives produced by male authors about her.

Dr. Havlioğlu started her lecture by recounting her academic journey, which began with her encounter with the late Walter Andrews while she was a student at Bilkent University. Following this influential meeting, she decided to specialize in Ottoman poetry, questioning the role of woman poets within Ottoman literature. Through her research with Walter Andrews at the University of Washington to trace female poets, Dr. Havlioğlu wrote her Ph.D. dissertation on Mihrî Hatun, which she later developed into an academically stimulating book titled Mihrî Hatun: Performance, Gender-Bending, and Subversion in Ottoman Intellectual History (2017). Despite the scarcity of written documents about woman poets prior to the 19th century, Dr. Havlioğlu thoroughly presented Mihrî Hatun's life as a woman poet as well as her strategies of subversion and integration within the courtly literary tradition.

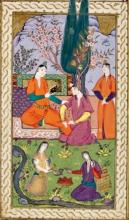

Regarding gender as inherently performative, Dr. Havlioğlu discussed the pre-modern expectations of manhood and womanhood in the male-dominated realm of Ottoman poetry. In this literary tradition, male poets commonly embody the roles of lover and beloved, thereby underscoring the androgynous characteristics of the ideal beloved and homosocial nature of Ottoman poetry. Dr. Havlioğlu persuasively argued that to navigate herself within these male homosocial literary networks, Mihrî Hatun also claims masculinity and deconstructs the traditional social construction of gender created by and for male poets. In doing so, Mihrî Hatun incorporates a heterosexual desire into her poetry, for instance, by associating herself with Zuleyha, a celebrated female lover. While this assertion challenges the male homosocial settings inherent, especially, in Ottoman literary gatherings (majlis), this intervention also enables Mihrî Hatun as a marginalized subject to be accepted within the male-dominated literary tradition, asserting her legitimacy and acknowledging her status among the male poets of her time.

Dr. Havlioğlu illustrated this recognition in literary domains by examining the portrayal of Mihrî Hatun’s life and poetry in several bibliographical dictionaries of poets (tazkirah). These entries proved to be one of the most valuable primary sources to trace the male (mis)conceptions and (mis)perceptions of woman poets in the early modern Ottoman Empire. In these narratives written exclusively by men, Dr. Havlioğlu highlighted the consistent narrative around Mihrî Hatun’s marital status, virginity, and prurient gossip about her romantic life, suggesting these male intellectuals regard Mihrî Hatun as a woman before recognizing her as a poet. Depicting Mihrî Hatun as a respectful and chaste woman, these accounts generally combine humor with an erotic desire for this female poet, leading to her marginalization.

Despite later male authors characterizing Mihrî Hatun in such terms, she utilizes several concepts typically associated with men, such as manliness, courage, and bravery, in her poems to survive in this gendered poetic arena, as Didem Havlioğlu put forward. One of the exemplary instances of this transgressive imagery is “They say your rival boasts and says, ‘I will kill her one day’ / If he is a man, let him come, and I will show manliness to that unmanly coward.” Dr. Havlioğlu also provided several other examples from Mihrî Hatun’s poems to illustrate how she challenges societal norms and gender structures by effectively manipulating language and traditional poetic discourse. For instance, Mihrî Hatun resists the prevailing degrading beliefs of women by stating, “Since they say women lack reason / All their words should be excused,” which shows that Mihrî Hatun does not believe there is a relation between intelligence and gender. Consequently, Dr. Havlioğlu asserted that the marginalization of women results in women’s continual subversion and transgression through defiance of social expectations for women, as successfully exemplified by Mihrî Hatun.

The day after the lecture, Dr. Havlioğlu met with UW graduate students to further discuss Mihrî Hatun’s poetry and her strategies of gender-bending through a close reading of one of her poems. Selecting a poem from Mihrî Hatun’s collection, Dr. Havlioğlu invited the students into a literary discussion. Interpreting the poems not only as literary pieces but also as historical documents, she emphasized the use of Mihrî Hatun’s colleagues’ names, such as Makâmî, to legitimize her poetic skills. Furthermore, Dr. Havlioğlu examined the humorous elements of the poem as a tool to challenge and subvert gender norms and traditional poetic imagery in Ottoman literature. She argued that this erotically humorous discourse creates a Bakhtinian carnivalesque effect, enabling Mihrî Hatun to criticize social norms. Dr. Havlioğlu concluded that Mihrî Hatun resists the role of the passive beloved and establishes herself as an active poet, further suggesting that Mihrî Hatun successfully criticizes social limitations for women by manipulating the traditional aesthetic structures and language.

Overall, during her lecture and meeting with graduate students, Dr. Havlioğlu deftly demonstrated that women were a part of intellectual circles in the early modern Ottoman Empire through the example of the celebrated woman poet Mihrî Hatun. Despite poetry commonly being regarded as a male domain, evidence suggests that women were still involved in this gendered realm. Dr. Havlioğlu richly illustrated how, even though male intellectuals and poets sideline Mihrî Hatun due to her gender, she persistently employs various transgressive strategies to legitimize her status as an active poet, as detailed above. Moreover, Mihrî Hatun’s portrayal in tazkirahs underscores that the history of Ottoman literature predominantly reflects the perspectives of powerful men and elite literati. However, Dr. Havlioğlu resituated Mihrî Hatun through close engagement with her poetry, offering alternative avenues to write literary histories and prompting us to scrutinize this centuries-long literary tradition not in terms of uniformity, but rather nuances. Finally, Dr. Havlioğlu pointed out the importance of exploring non-canonical voices, as the concept of canon imposes inevitable limitations. Undoubtedly, woman poets, non-canonical authors, and marginalized intellectuals contribute to the richness of Ottoman literature, offering historically more accurate insights into its various layers.