By Kathryn Medill

I vividly remember one of my early encounters with Ancient Middle Eastern Studies. The class was reading a letter in the Akkadian language by a man who was far from home. He wrote to a friend, complaining that he was homesick for the foods he used to eat. I was immediately sympathetic, since I had just started a new graduate program in a new place. His story reminded me that, even though the details of human experiences change constantly, certain aspects of human experience are universal. In a Maryland classroom in 2015, I could connect with a person who had lived thousands of miles away and thousands of years ago.

By the way, the food he missed the most? It was cooked mole rat!

We can learn about the stories of people from long ago through art, archaeology, and text.

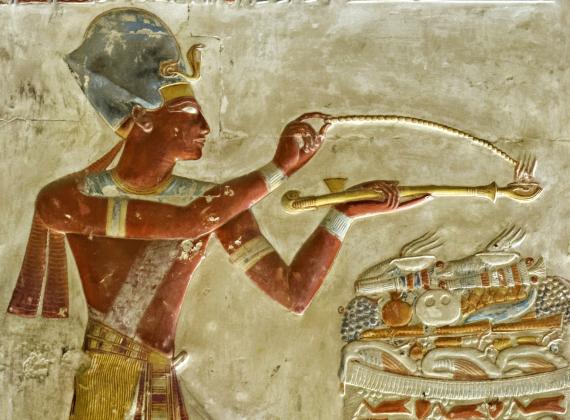

For example, much of what we know about ancient Egyptian religious life comes from art! This picture from the mortuary temple of King Sety I in Abydos shows the king of Egypt in his blue crown. He stands in front of an incredibly detailed table full of food items, meant as offerings to the sacred boat of the god Amun-Ra, and puts beads of incense into the fire on a long golden censer. In this image, meant to remain forever in the king’s mortuary temple after his death, Sety continually worships the gods, expressing his eternal piety and humility—which will, he hopes, lead to their continual blessing and protection in the afterlife!

Want to learn more about ancient religion? Check out MELC 302/502, “Religions of the Ancient World,” next offered Autumn 2026!

Archaeology can tell us all kinds of things about ancient lives. Whether we discover towers, palaces, homes, religious sites, trash pits, or burial areas, they all have stories to tell. For instance, I once visited the caves of Bet Guvrin. There I saw the olive processing sites which had been discovered and reconstructed by archaeologists. I could immediately imagine the local community bringing their olives in baskets, making their way carefully down the white stone steps into the caves. In the cool, broad space, they crushed the olives with small pairs of mill stones and took out the pits. Next, they pressed the crushed olives by using a tree trunk as a lever, hanging huge stones on the trunk to compress the olives more and more, collecting the oil in jars set at the ends of sluices carved directly into the stone. The community would use the fine oil of the first pressing in cooking, while they used later, grittier pressings in hygiene and cosmetic products, as well as in oil lamps.

Want to hear more of the stories that archaeology can tell us? Join MELC 313/513, “Ancient Technologies of the Near East” in Spring 2026; or MELC 209, “Introduction to Ancient Near Eastern Archaeology,” in Autumn 2026.

Finally, we can connect with people’s lives and stories through texts. Here’s a letter that two sisters in the great trade city of Assur wrote to their brother, who had been away from home for years running the Anatolian end of the family trading business.

Dear Imdi-ilum,

Thus say (your sisters) Taram-Kubi and Simat-Assur!

We went to the women who interpret dreams here, the female diviners, and the ghost-speakers, and the god Assur warns you (through these omens)! (He says,) “You love money too much! You don’t care for your life!” Can’t you make the god Assur happy here in the City? Please, when you have had this letter read to you, come here, see the Eye of Assur and save your life!

By the way, why don’t you send me the money you got from selling the cloth I made?

The sisters are worried about their brother’s relationship with Assur, the king of the Assyrian gods—but they also want to be paid for their work!

Do you want to connect with more real ancient women like Taram-Kubi, or learn about women’s views of the world through ancient fiction? Enroll in MELC 308/508, “Women in the Ancient Middle East,” next offered Autumn 2026; or MELC 308/507, “From Israelites to Jews: 586 BCE to 70 CE,” offered Spring 2026!